The history books overlook the significant role Mexico played in providing a sense of safety for enslaved people. The country often spoke out against slavery and the freedom they offered.

In 1829, Vicente Guerrero, who was of African descent, abolished slavery in Mexico— just 34 years before Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Mexico freed over 200,000 enslaved people and opened a pathway for enslaved Africans seeking freedom. One of the many paths was the Rio Grande.

Texas, which was once a part of Mexico, was heavily populated with white enslaver, leading to the Texas Revolution. The Revolution birthed the Republic of Texas, which officially turned into a state in 1845 where they began to enslave Africans again.

Most of us are familiar with the northern underground railroad and how people like Harriet Tubman led them to safety or how others sheltered enslaved people in their homes. However, enslaved people traveling south went through rough terrain, rivers, and pathways to finally reach the end destination, Rio Grande. When they crossed over the muddy waters, they were free.

It is estimated that 5,000 to 10,000 enslaved men and women escaped through the Rio Grande pathway. While the majority came from Texas, individuals from North Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama were also said to have escaped to Mexico, using the southern underground railroad.

Those who were caught, were killed and lynched. There aren’t many records about the southern routes and how exactly they managed to learn them. However, it has been said that local Tejanos (natives of Mexico), as well as recently freed persons who resided in Mexico, assisted along the way.

“I’m very proud to be a Webber,” 70-year-old Olga Webber-Vasques said to NPR, after her daughter-in-law uncovered part of her family’s history. She recently discovered her great-great-grandparents had a hand in the underground railroad, the path that went from South Texas to Mexico. Thousands of enslaved people escaped plantations through “The River of Deliverance”.

“I don’t know why there wasn’t anything that we would’ve known as we were growing up. It amazes me to learn the underground deal — I had no idea at all.”

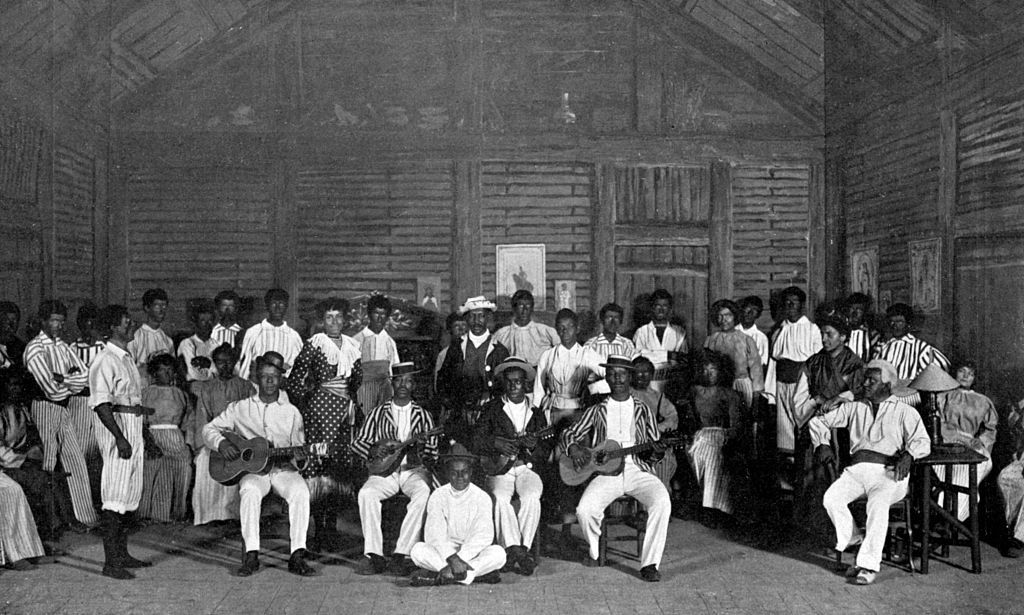

Escaped slaves adopted names of native Mexicans, married into Mexican families, or migrated deeper into Mexico— causing them to disappear from any records or history. From the records that do exist and with the help of Roseann Bacha-Garza, a program manager of the Community Historical Archeological Program with Schools at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, we know of a man named Nathaniel Jackson.

Nathaniel Jackson, who’s father was an enslaver and his mother an enslaved woman, along with his wife Matilda Hicks— an enslaved woman at Nathaniel’s father’s plantation— moved to South Texas to raise their kids. When they settled in San Juan on a ranch, they used their home and property as a safe haven where they housed, clothed, fed, and guided enslaved Blacks into Mexico. They helped transport people onto the trade ferries for their crops and cattle, along the Rio Grande and eventually landing in Mexico.

“Mexican authorities at times would help the now-free men and women in Mexico from being taken and returned to the United States,” says Maria Hammack, a doctoral candidate at the University of Texas at Austin and currently writing her term paper on the Webber family.

While this important piece of history is still not being share enough, students in Texas schools are now beginning to learn this missing piece of history and the impact Mexico truly had on United States history.