In the late 1960s, a Black lawyer had the vision to build a city that would take the idea of Black capitalism and personify it through owning businesses, factories, land, an airport and so much more. He would call it Soul City

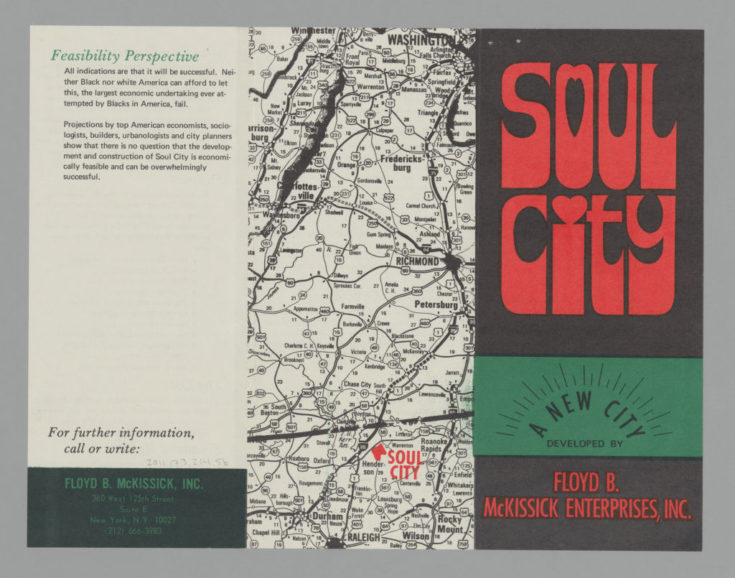

Floyd McKissick purchased 1,800 acres of undeveloped land in North Carolina to build “Soul City” a place he dreamed would serve as the capital for “Black capitalism,” as the New Yorker called it.

McKissick was the leader of the Congress of Racial Equality, also known in the mid-’60s as CORE: one of the organizations known to be a leading proponent of Black power. McKissick believed that one of the most important components of Black power was having economic power.

CORE was founded in 1942 as a way to fight segregation and by the time McKissick started leading the organization, he had been known as an accomplished integrationist.

He was one of the plaintiffs in the N.A.A.C.P’s case in 1951 that forced U.N.C. to change its policies and accept McKissick into its law school. UNC barred Black students at the time. And in 1959, two of his children enrolled at a previously all-white public school in Durham, as the New Yorker points out.

By 1966, he was leading CORE and in his new role, he joined the March Against Fear where he joined Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Stokely Carmichael in a walking protest through Tennessee and Mississippi.

Two years later, he was in Cleveland trying to convince white business owners to build factories in the city of Cleveland’s “ghetto” neighborhoods. His idea was that once the factories had recouped their initial investments, that Black workers could assume ownership. On that same day, April 4, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated and McKissick responded with anger.

“Nonviolence is a dead philosophy,” he told the Times, “and it was not the Black people that killed it.”

Moving On To Promote Black Wealth

Months after Dr. King’s death, McKissick left CORE to start a new venture known as McKissick Enterprises, which promised Black Economic Power. He promised to invest in everything from restaurants to book publishing, it was he called the “last chance to save the Republic.”

For him, he was done with marching and was ready to build.

Shortly after launching McKissick Enterprises, he announced that he would build Soul City: a new town designed by and for Black people. While he promoted the town as a place ‘open to all races,” he made sure to point out that it would be a place where “Black people can come, and they’re wanted.”

Thomas Healy, the author of a new book called Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia told NPR that while serving in the military after World War II, watched how French planners and engineers were rebuilding their cities after they were destroyed by shelling. Healy went on to explain that his thought process was, ‘if people in Europe could rebuild their cities, why couldn’t Black people in America build new cities from scratch?”

Healy went on to explain that McKissick envisioned Soul city having around 50,000 residents by 2000 across 5,000 acres. Because it would’ve been built from scratch, the infrastructure would’ve been newer as well, including the idea of bike paths and walking paths to nature.

In the summer of 1972, Healy explains in The Atlantic that the Nixon administration awarded Soul City a $14 million loan guarantee to prepare the land for development, which means McKissick’s dream appeared to be within arm’s reach.

The loan was part of a federal program financing 13 new communities across the country. Soul City, however, was the only project in a rural area and the only one led by a Black developer, as Healy points out. At the same time, McKissick changed his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican and endorsed Richard Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign because he thought it was necessary to guarantee government support.

At one point, Soul City gained both momentum and enthusiasm.

Healy says major corporations, including General Motors, took interest in building factories in the town and at the time, the governor of North Carolina offered financial support. In just a few years, the Soul City project had a staff of 70 people, and the population was starting to grow as the new city had at least 100 residents.

Soul City never really came to be because it lacked financial backing. Sure, other new cities at the time survived at the time such as The Woodlands in Texas; Columbia in Maryland, and Reston in Virginia. The difference is that these cities were built by white developers and financed by white corporations, as Healy points out.

For many people, Soul City is the Utopia that never was. Today, the town itself is not shown on a map, and now a private homeowners’ association has taken its place.

But its story and the message behind Soul City is relevant, if not more than ever today as it highlights the need for more investment in Black communities and the need for more Black-owned businesses so entrepreneurs are not dependent on white institutions for support, as Healy points out.