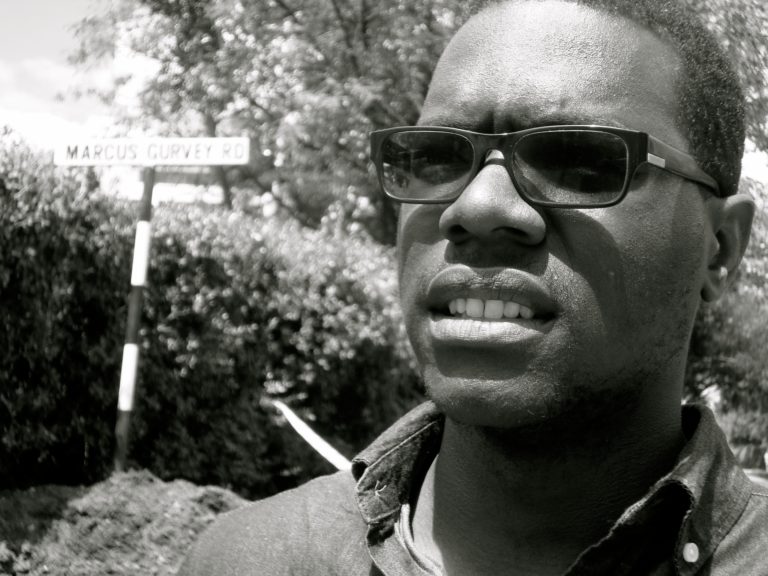

I was the first black American that my Kenyan host family had ever accommodated in the four years they had served as a home-stay for travelers in Nairobi. It was a strange brew of emotions to be a black American in Africa. While I enjoyed the feeling of acceptance, I felt pressure to represent my community on a global scale.

My white peers in my study abroad program, however, experienced what it was like to be an “other” and were quickly noticed as different and treated as such. Novice travelers have the tendency to see the environment as dangerous and can feel alienated by the new attention they receive from Kenyans who label them “Mzungu” or white person. I, however, felt incredibly welcomed and found a sense of peace being surrounded by people who look like me.

For the first time in my life, I was in a society that wasn’t segregated by ethnic zone. For once, I felt truly anonymous. I was wary of the potential for criminal activity in Kenya, but that the vast majority of people initially assumed I was a fellow Kenyan and not a black American.

It was my American attitude and accent that gave me away. As soon as I spoke, I became an “other” as well, but a different kind of other. Being a black American in Africa is a psychological tightrope where a sense of identity is intermittent vertigo. I was both a part of and apart from, the people.

Unlike in America, in Nairobi, being dark-skinned had advantages. I walked the streets with minimal hassle from others, while those with light skin were hassled verbally and repeatedly asked to buy goods. Call it pressure or privilege, but as a black American in Africa, I met many young Africans that never had the opportunity to meet an African American, putting me in a unique position as a traveler to where I felt like the voice for black America.

RELATED: My Black Card Was Revoked

One weekend in Nairobi, I met a Kenyan girl about my age who asked me if I was African American. I told her yes. She responded, “Like you grew up in America?” I smiled and said yes: she made being from the United States sound so unique. She then told me that my accent didn’t sound the way she expected black Americans to sound. I chuckled and told her that we don’t all sound the same.

We shared a laugh about it, but her comment reminded me of the limited perceptions people abroad are receiving about black Americans and concerned me about the limited perspective they get about black Americans. How are Africans in Nairobi and across the continent learning about Africans in America and who are they learning from?

The answer is white men. I conversed with a member of the church I attend about his perspectives on black Americans: where he gets them from, etc. He told me that usually, he would hear about them through white missionaries who were visiting Kenya who shared perspectives like:

Black American women are rude and incorrigible and black Americans are generally dangerous, lazy and short-term thinkers.

These were some of the perspectives from young and old people traveling ostensibly in Kenya to spread the word of Christianity. The brother I was talking to assured me that he listens to their words with a careful ear and does not simply accept everything they say.

He posed an interesting question to me after we discussed the perspectives. Speaking on behalf of other Kenyans he had spoken to, he asked why haven’t more African Americans developed an interest in at least visiting Africa and doing evangelism. He explained that Africans do not want to hear that their brothers in America are failing.

I shared that I was glad he took the words in stride because all the comments were one-dimensional stereotypes of black Americans coming from men who most likely had very limited encounters with black Americans in general.

The danger of these views is that they are not holistically understood but rather severely limited in scope. So I provided a counterpoint to the discussion. I talked with him about the amazing black women in my life and I explained how the need to control black people and their reputation is historically and contemporaneously a result of colonialism.

Ultimately, I left the conversation feeling that as African Americans, we do need to make stronger efforts to connect with our brothers and sisters in Africa. Not only to treat the poisonous perspectives spewed by media and missionaries, but also to use the critical insights of cross-cultural knowledge.

Exploring what it means for others to be African has globalized my perspective of what it means to be a black American, how others see me and my power to shape that lens. Traveling has put me in a place of power where I can offer counter perspectives, serving as an ambassador for myself and my people.